Henrietta’s Legacy: The Case for Informed Consent in Research

Oct 2, 2025

In 1951, Henrietta Lacks, a young Black woman seeking treatment for her cervical cancer at Johns Hopkins Hospital, had her tumor cells stored without her knowledge or permission. Those cells became the first immortal human cell line - HeLa cells - propelling breakthroughs from developing the polio vaccine to cancer therapies, gene mapping, and even COVID-19 research. Her contribution to science is immeasurable - but it came at the cost of her consent and her family’s trust.

Henrietta’s story is more than history. It is a living reminder that scientific progress must never come at the expense of patients’ autonomy and dignity.

What Henrietta Taught Us About Consent

When I reflect on Henrietta’s Legacy, two lessons stand out:

- Transparency matters. She never knew her cervical cancer specimens were being kept, propagated, and distributed around the world. That lack of communication was a profound violation of her privacy.

- Exploitation must be avoided. For decades, HeLa cells generated billions in profit. Henrietta and her family received nothing - a stark reminder of how easily patients’ contributions can be commodified without ethical guardrails.

These lessons shaped how we built Reference Medicine. From the start, we decided that informed patient consent would be our foundation.

How Informed Consent Works in Practice

Most people don’t realize they can donate specimens during their lifetime. In fact, many patients who undergo biopsies or surgeries have leftover tissue or blood that could advance science.

One of my colleagues, who is a cancer survivor, shared that despite multiple biopsies and surgeries, no one ever mentioned specimen donation to her. She assumed, like many, that donation was only possible after death. That gap in communication shows how much work remains to make patients aware of this option.

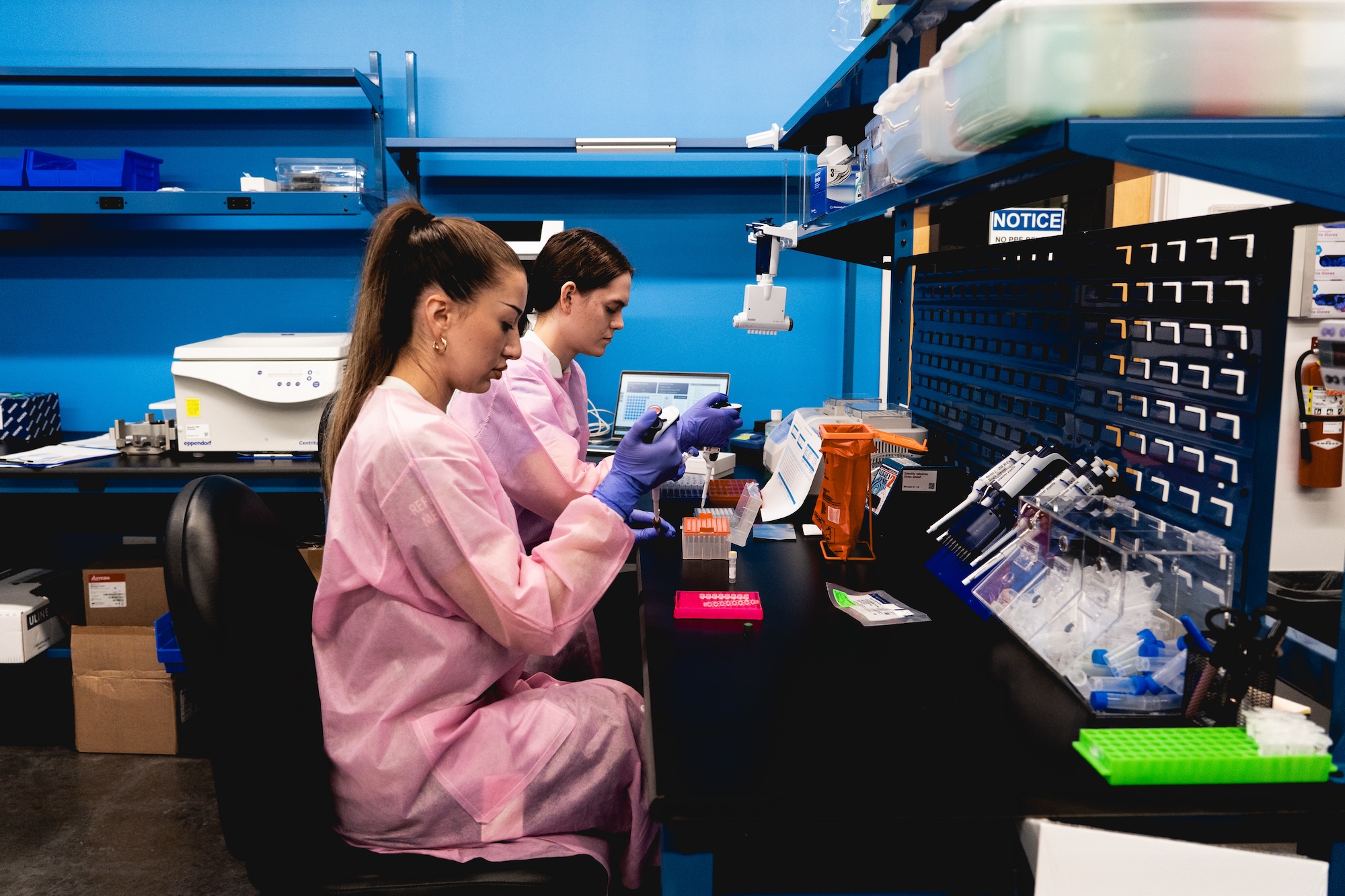

At Reference Medicine, we’re working to change that. Our hospital partners approach patients before surgery, not using a quick signature buried in fine print, but a detailed, seven-page consent document read aloud by a nurse or research coordinator. It covers everything - from the possibility of genomic sequencing, to the fact that our work is commercial, to the limits of privacy protections. Patients know exactly what they’re saying yes - or no - to.

Where the Industry Still Falls Short on Patient Consent

Today, roughly 95% of human biospecimens used in research come from “passive consent” models - pulled from archives, leftover from tests, or authorized by vague hospital intake language. Most patients have no idea their tissues are being used for research purposes.

The impact falls hardest on marginalized communities. Historically, Black and brown patients were more likely to have specimens taken without consent. Now, because robust consent processes are concentrated in large, well-funded hospitals, minority patients are often underrepresented in research altogether.

Both exploitation and exclusion remain pressing challenges.

What Ethical Biospecimen Procurement Looks Like

At Reference Medicine, we are committed to three pillars of ethical biospecimen procurement:

- Informed Consent. All of our prospective collections have explicit patient consents.

- De-identification and Security. We never know who the patient is; hospitals retain that information. We only receive de-identified samples.

- Transparency. We share consent templates and processes with researchers and price specimens based on actual work - not inflated margins.

For researchers, here are three questions worth asking before accepting specimens:

- Was patient consent obtained?

- Can I review the consent form?

- Who processed the specimen, and under what oversight?

If a procurement company can’t - or won’t - answer, that’s a red flag.

A Call for Transparency

Henrietta’s story reminds us of what is lost when patients are left out - and what can be gained when they are invited into the research process. Transparency doesn’t slow down science; it strengthens it. When patients understand how their contributions will be used, they are more willing to give.

At Reference Medicine, we hold fast to one belief: every specimen has a story. The least we can do is honor it. And, that is precisely what we do.